The 15th Amendment was supposed to guarantee Black men the right to vote, but exercising that right became another challenge.

Updated: April 15, 2021 | Original: January 29, 2020

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, the United States found itself in uncharted territory. With the Confederacy’s defeat, some 4 million enslaved Black men, women and children had been granted their freedom, an emancipation that would be formalized with passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution.

For Black Americans, gaining the full rights of citizenship—and especially the right to vote—was central to securing true freedom and self-determination. “Slavery is not abolished until the Black man has the ballot,” Frederick Douglass famously said in May 1865, a month after the Union victory at Appomattox.

After Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, the task of reconstructing the Union fell to his successor, Andrew Johnson. A North Carolina-born Unionist, Johnson believed strongly in state’s rights, and showed great leniency toward white Southerners in his Reconstruction policy. He required the former Confederate states to ratify the 13th Amendment and pledge loyalty to the Union, but otherwise granted them free rein in reestablishing their post-war governments.

As a result, in 1865-66, most Southern state legislatures enacted restrictive laws known as Black codes, which strictly governed Black citizens’ behaviors and denied them suffrage and other rights.

Black CodesRadical Republicans in Congress were outraged, arguing that the Black codes went a long way toward reestablishing slavery in all but name. Early in 1866, Congress passed the Civil Rights Bill, which aimed to build on the 13th Amendment and give Black Americans the rights of citizens. When Johnson vetoed the bill, on the basis of opposing federal action on behalf of formerly enslaved people, Congress overrode his veto, marking the first time in the nation’s history that major legislation became law over a presidential veto.

With passage of a new Reconstruction Act (again over Johnson’s veto) in March 1867, the era of Radical, or Congressional, Reconstruction, began. Over the next decade, Black Americans voted in huge numbers across the South, electing a total of 22 Black men to serve in the U.S. Congress (two in the Senate) and helping to elect Johnson’s Republican successor, Ulysses S. Grant, in 1868.

The 14th Amendment, approved by Congress in 1866 and ratified in 1868, granted citizenship to all persons “born or naturalized in the United States,” including former slaves, and guaranteed “equal protection of the laws” to all citizens. In 1870, Congress passed the last of the three so-called Reconstruction Amendments, the 15th Amendment, which stated that voting rights could not be “denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Reconstruction saw biracial democracy exist in the South for the first time, though much of the power in state governments remained in white hands. Like Black voters, Black officials faced the constant threat of intimidation and violence, often at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan or other white supremacist groups.

Fifteenth AmendmentWhile the 15th Amendment barred voting rights discrimination on the basis of race, it left the door open for states to determine the specific qualifications for suffrage. Southern state legislatures used such qualifications—including literacy tests, poll taxes and other discriminatory practices—to disenfranchise a majority of Black voters in the decades following Reconstruction.

As a result, white-dominated state legislatures consolidated control and effectively reestablished the Black codes in the form of so-called Jim Crow laws, a system of segregation that would remain in place for nearly a century.

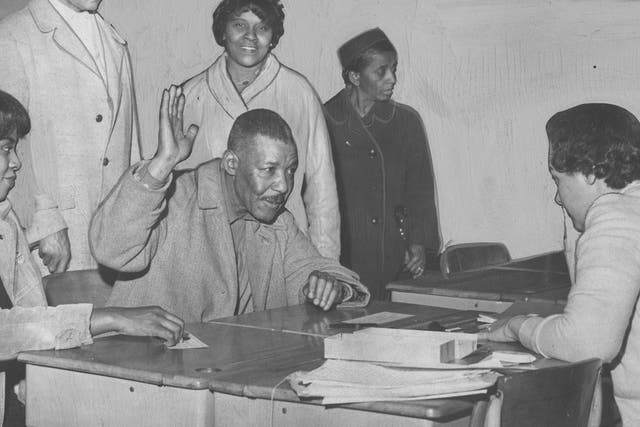

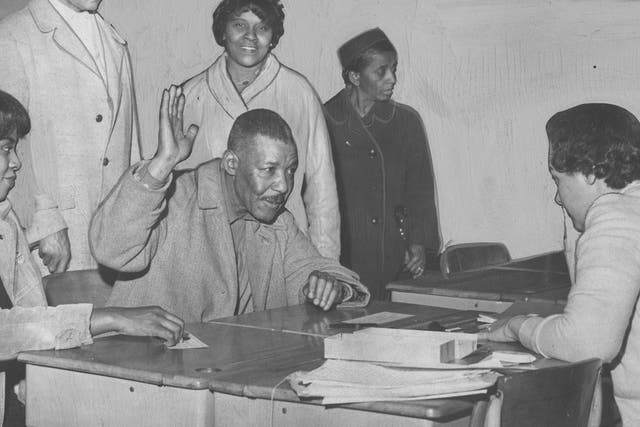

In the 1950s and ‘60s, securing voting rights for African Americans in the South became a central focus of the civil rights movement. While the sweeping Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally banned segregation in schools and other public places, it did little to remedy the problem of discrimination in voting rights.

The brutal attacks by state and local law enforcement on hundreds of peaceful marchers led by Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights activists in Selma, Alabama in March 1965 drew unprecedented attention to the movement for voting rights. Later that year, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act, which banned literacy tests and other methods used to disenfranchise Black voters. In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections that poll taxes (which the 24th Amendment had eliminated for federal elections in 1964) were unconstitutional for state and local elections as well.

Before passage of the Voting Rights Act, an estimated 23 percent of eligible Black voters were registered nationwide; by 1969 that number rose to 61 percent. By 1980, the percentage of the adult Black population on Southern voter rolls surpassed that in the rest of the country, the historian James C. Cobb wrote in 2015, adding that by the mid-1980s there were more Black people in public office in the South than in the rest of the nation combined.

In 2012, turnout of Black voters exceeded that of white voters for the first time in history, as 66.6 percent of eligible Black voters turned out to help reelect Barack Obama, the nation’s first African American president.

In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, ruling 5-4 in Shelby v. Holder that it was unconstitutional to require states with a history of voter discrimination to seek federal approval before changing their election laws. In the wake of the Court’s decision, a number of states passed new restrictions on voting, including limiting early voting and requiring voters to show photo ID. Supporters argue such measures are designed to prevent voter fraud, while critics say they—like poll taxes and literacy tests before them—disproportionately affect poor, elderly, Black and Latino voters.

Sarah Pruitt is a writer and editor based in seacoast New Hampshire. She has been a frequent contributor to History.com since 2005, and is the author of Breaking History: Vanished! (Lyons Press, 2017), which chronicles some of history's most famous disappearances.